Back underground... at the Paris Catacombs

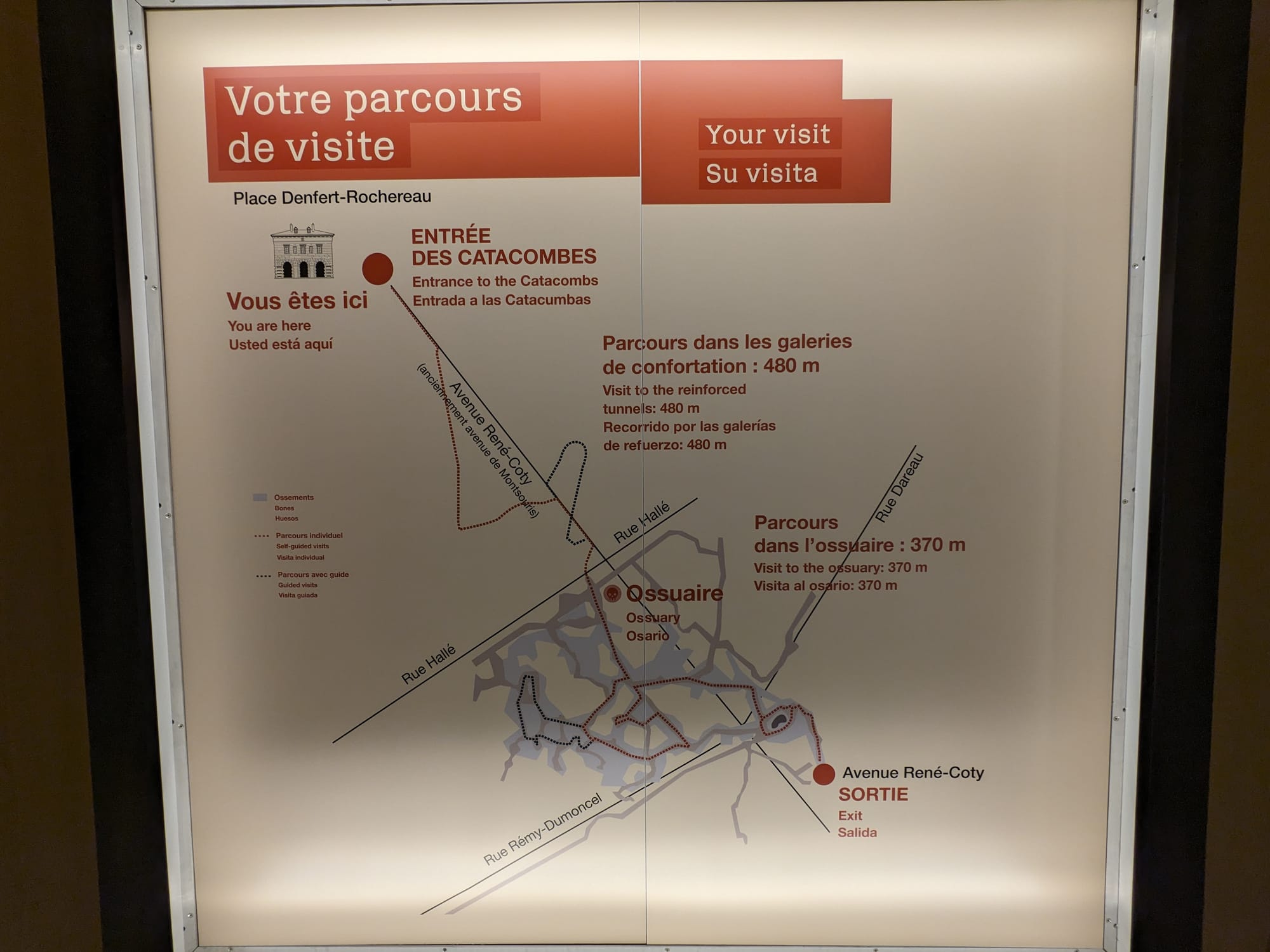

For our first expedition on our busy Tuesday in Paris, we headed to the Paris Catacombs. More properly an ossuary (bone yard), A and I had tried to get here on two previous visits (note for fellow travellers: the catacombs are NOT open on Mondays — ever!).

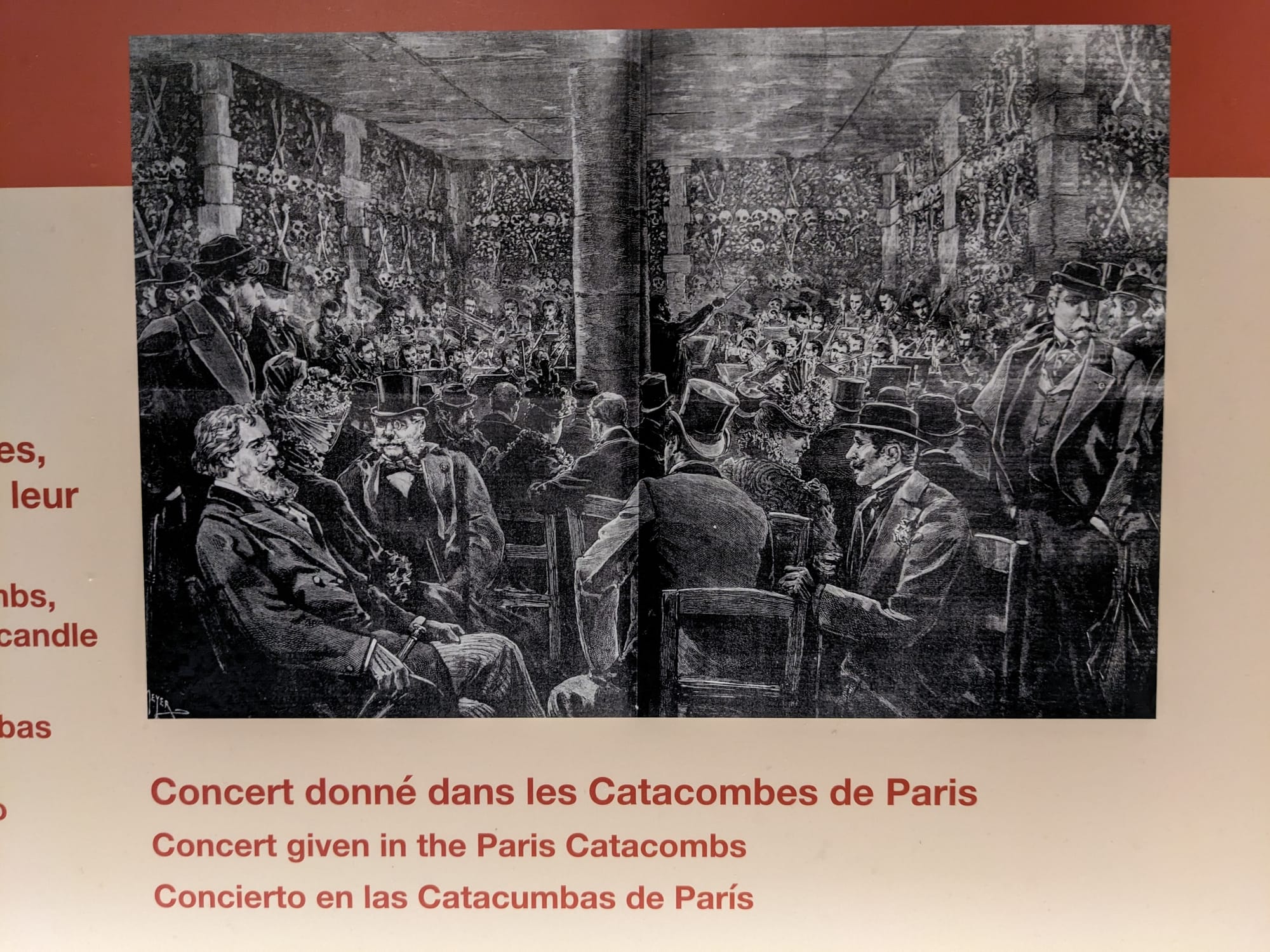

Open to the public since the early 1900s (and to visiting dignitaries and clandestine concertgoers before that), the catacombs hold the bones of millions of Parisians from the 10th to the 18th centuries. Almost none of the remains are individually identified, though some famous inhabitants (including, for the science nerds out there, Antoine Lavoisier), are at least known to be among the bones.

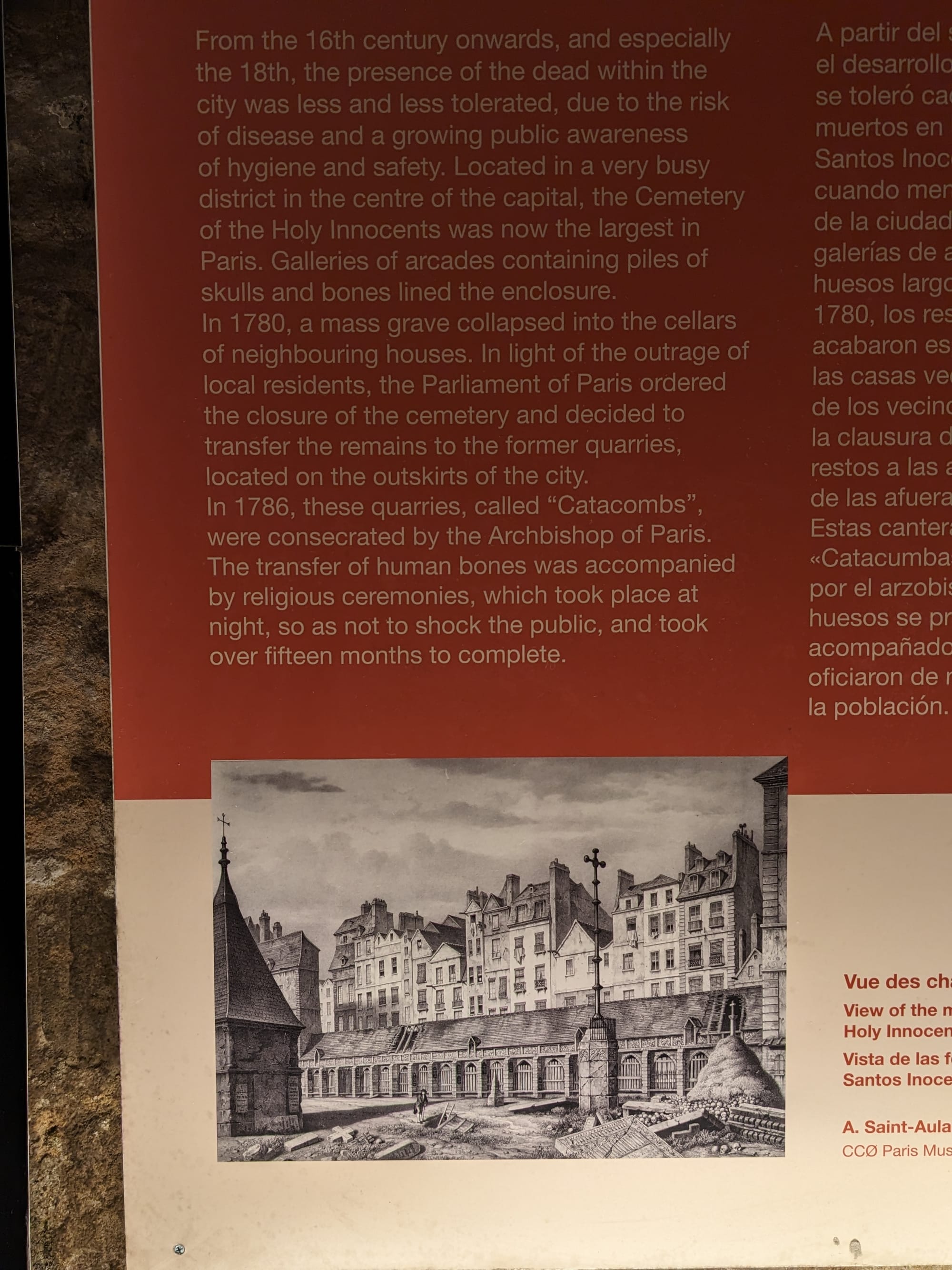

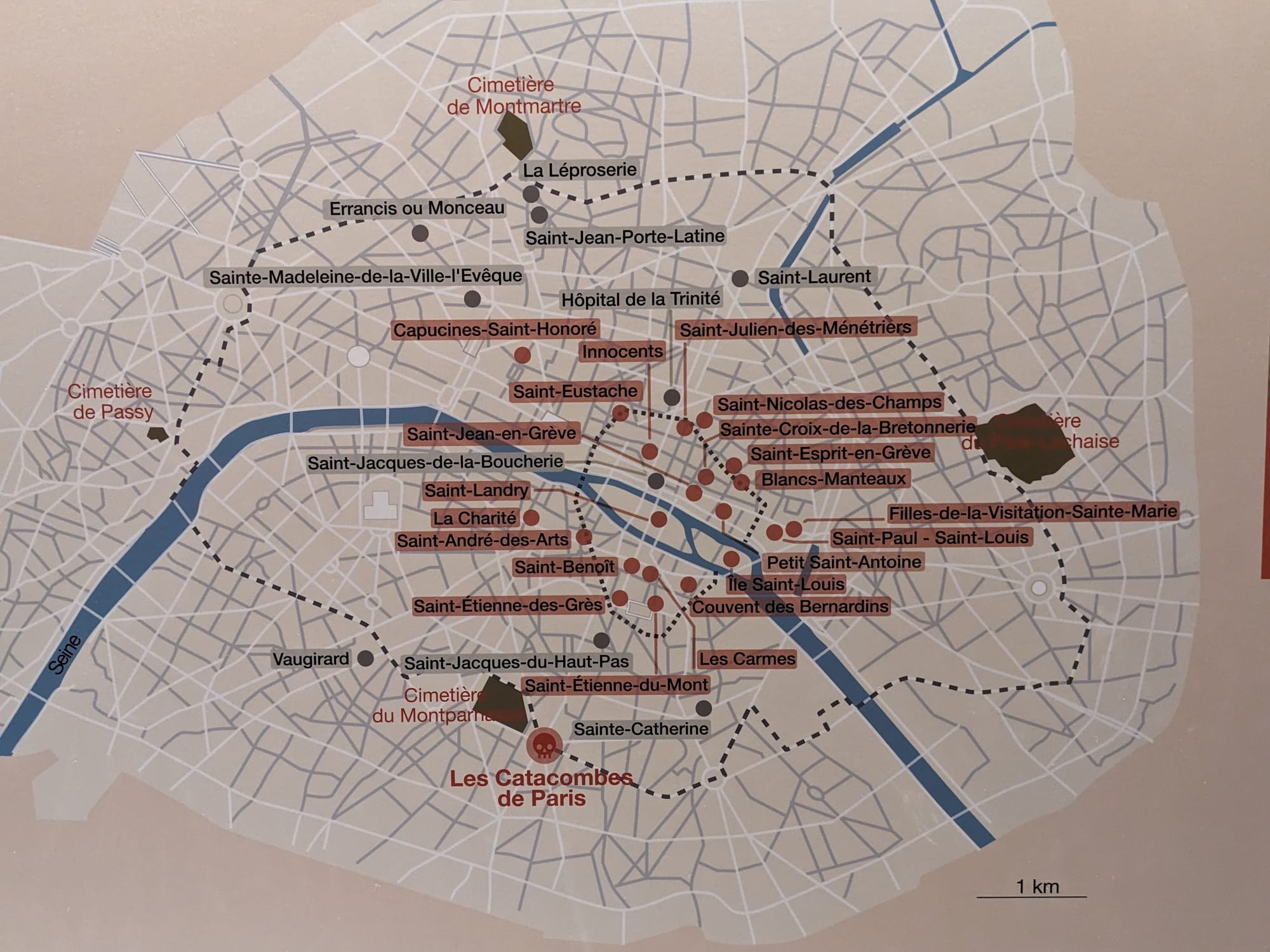

This is because the vast majority of the bones interned in the catacombs are from former graveyards (mostly paupers' mass graves, but more important ones as well) that were exhumed and reburied in the catacombs between the 1780s and 1860s. This was in part to address health and safety issues, including mass graves collapsing into nearby basements and cellars.

At the time, all graveyards within the Paris city limits were exhumed and transfered to the catacombs. Four new graveyards were established outside the city. The catacombs themselves are actually old limestone quarries which were the source of building material for Paris's many limestone edifices, including the Louvre and Notre Dame. Quarrying was stopped after some significant building collapses and sinkholes.

The Inspectorate-General of Quarries was established to shore up and make them safe — and continues that role today. It also managed the relocation of remains and is responsible for conservation of the ossuary to this day.

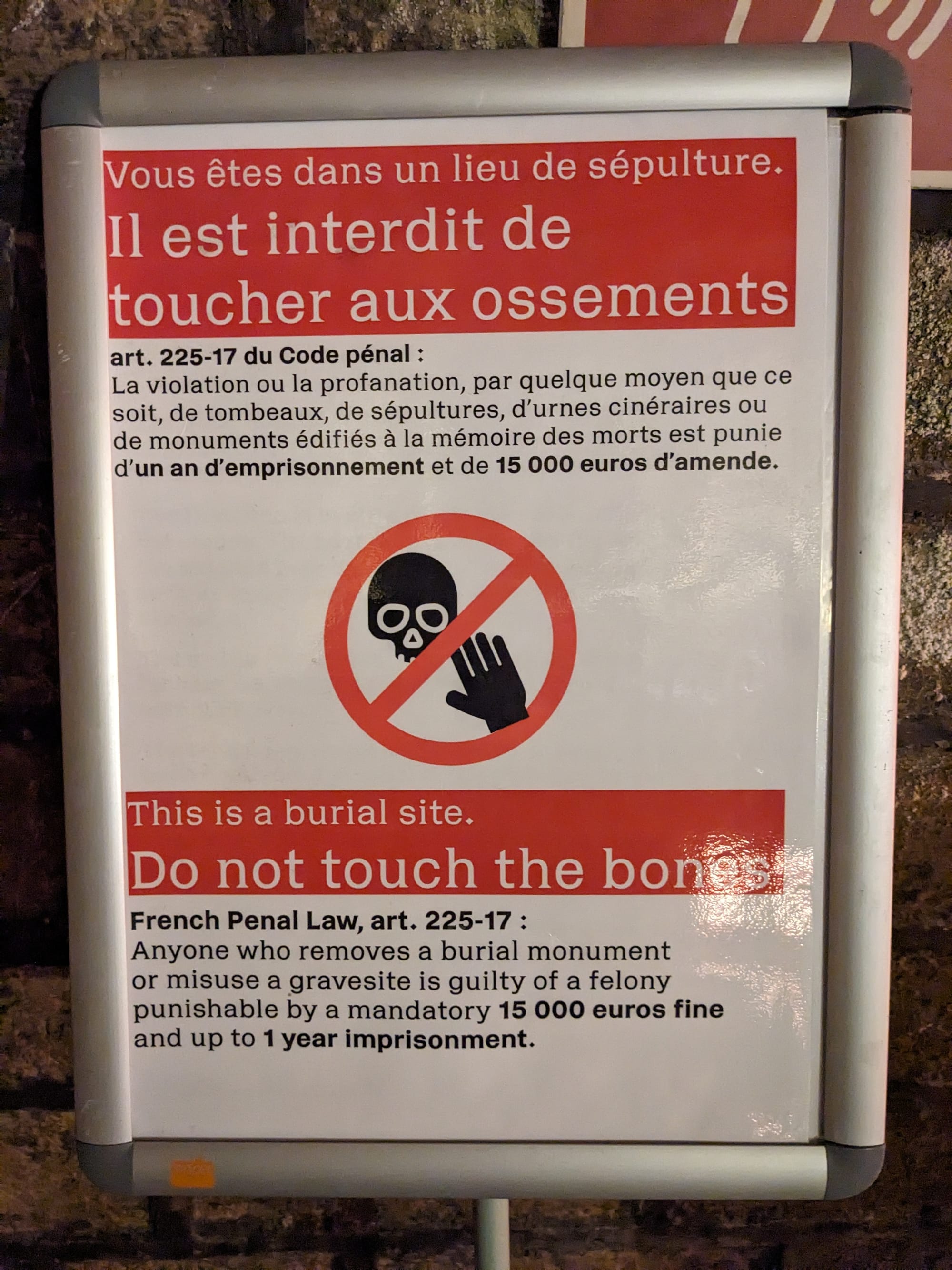

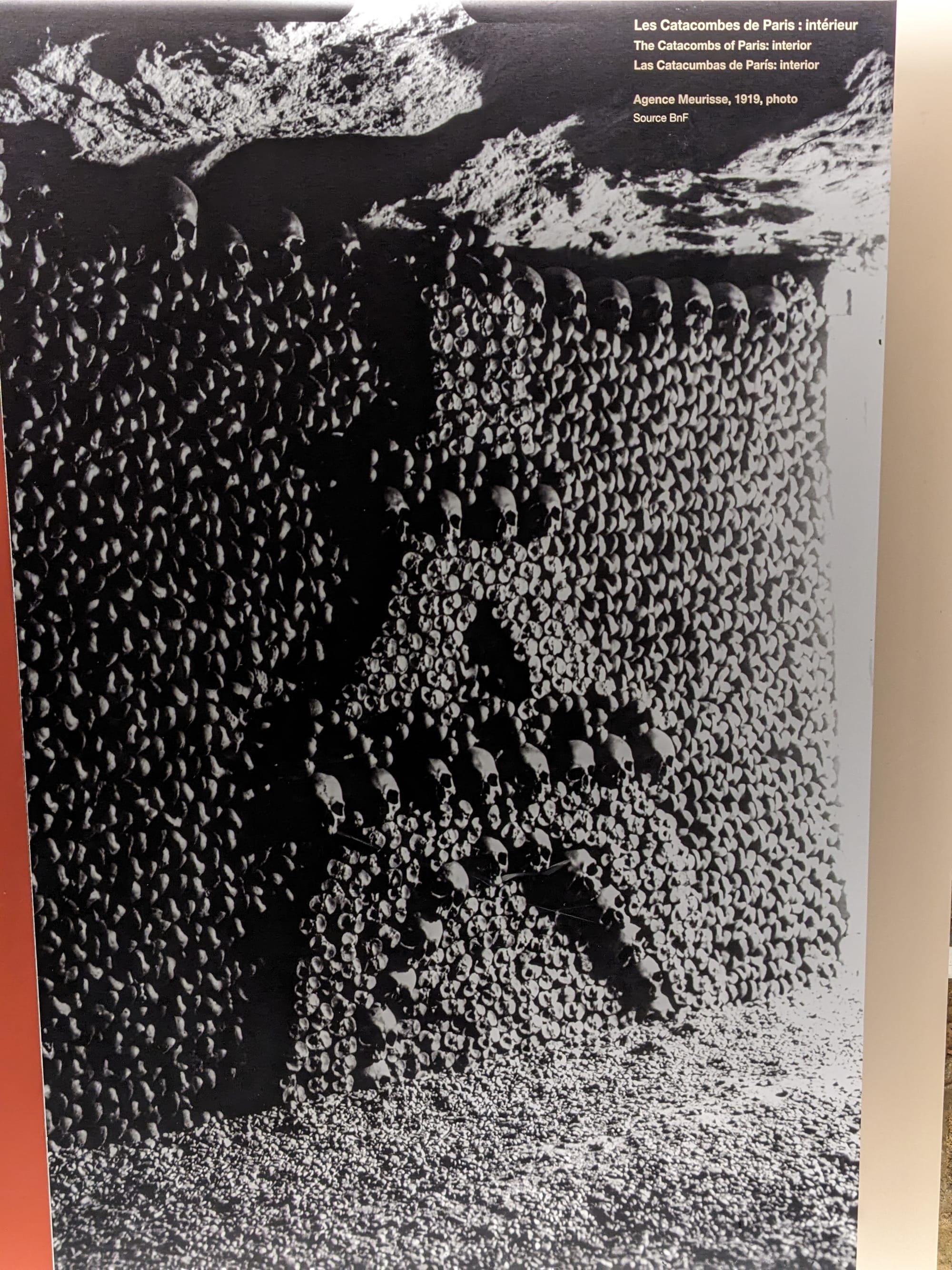

About 25m below the city, the ossuary is fairly sobering when you consider the millions of lives represented by the bones there. Many, especially skulls and femurs, have been formed into neat walls along the galleries of the the quarries. But behind those neat walls — many artistically arranged to form patterns of crosses, arches or just simply layers — are literal piles of assorted bones. While the exhumation and re-internment was carefully managed with considerable religious ceremony (at least until the French Revolution), the sheer volume allowed for little else.

It was a little incomprehensible to really take in the overwhelming number of lives and stories represented by what we could see. But still an interesting insight into how society relates to mortality and how this continues to change.